Fashion 👠

“Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.”

— Bill Cunningham

“You can have anything you want in life if you dress for it.”

— Edith Head

For costume projects, scroll through ⇵

Safavid Dynasty - Persian Empire Inspired Jacket

Safavid dynasty was one of the most powerful ruling dynasties of Persia (Iran). Shah Ismail I (1588-1629) founded the dynasty in 1501 and within 10 years of time took power over the entire Persia. The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 and controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Armenia, Georgia, North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Isfahan was the new capital after Shah’s accession in 1587. By the 17th century, Isfahan became the largest city in all of Safavid Persia because of the extensive network of production and distribution of raw silk and silk goods throughout Asia and Europe. Isfahan had 162 mosques, 48 madrasas, 1,802 caravansaries, 273 public baths, and 12 cemeteries within its boundaries. It was the home to a large Indian community—consisting of Muslims and Hindus—and their presence was particularly important from the perspective of commerce and trade.

Persian raw silk played a vital role in its economic history that was traded along the Silk Route from China to the Mediterranean. During the Safavid period, Shah made the production and sale of raw silk part of his economic and political strategy. In 1621, he founded a new port on the Gulf, Bandar Abbas (Gombroon). The English and Dutch established trading stations there.

The most important dress component during this century was the robe and turban for men and the čādor (a large piece of cloth that is wrapped around the head and upper body leaving only the face exposed, worn especially by Muslim women), as pronounced in Persian (chadar in Urdu) used for social customs and the performance of religious duties. The garments during that time did not survive due to the perishable nature of fine silks and cotton and also due to the burning of court garments to recover the gold and silver used in them. Among the best-represented survivals are men’s robes and women’s jackets from the 19th century.

Paintings were used as an important recording tool to show how various parts of the costumes were worn together along with manuscripts of that period. Documentation showed that women were usually veiled in public but few observers (until the late 19th century) were able to describe their attire from the previous centuries.

A typical Safavid costume comprised of layered garments in luxurious materials like gold and silver embroidered with organic shapes of birds, flowers, and animals, cut close to the torso and then spreading out in loose, flowing lines and worn with a variety of headgear, jewelry, ornaments, and accessories. The basic garments of men and women were almost interchangeable, except for the headgear: turbans and caps for men, veils for women.

During the 16th century, women wore a long, loose shirt with an opening to the waist in front, edged with contrasting fabric and fastened by a brooch. As the 17th century progressed, new variations in the basic dress were adopted. Men’s robes and women’s jackets became progressively shorter by that time.

A type of short jacket with sleeves came increasingly into fashion during the Safavid period, replacing the long jubbah (an ankle-length, robe-like garment, usually with long sleeves); it was worn wrapped across the chest and fastened at the sides. Although these changes were made during the reign of Shah, they are not commonly seen in miniature paintings and albums until after the mid-century.

During the 17th century, reeled cultivated silk was a natural product produced from the cocoons of silkworms. The rearing of silkworms to the cocoon stage was a labor-intensive process requiring many weeks of constant attention (Wulff, 1966). This process took place in a barn-like wooden structure where silkworm eggs were placed on wooden trays and left in the sun to begin the hatching process. After the hatching of the eggs, the silkworms ate mulberry leaves and within the next few days, they began to spin their cocoons, which were then used to extract out the silk by using a wheel-like spindle machine.

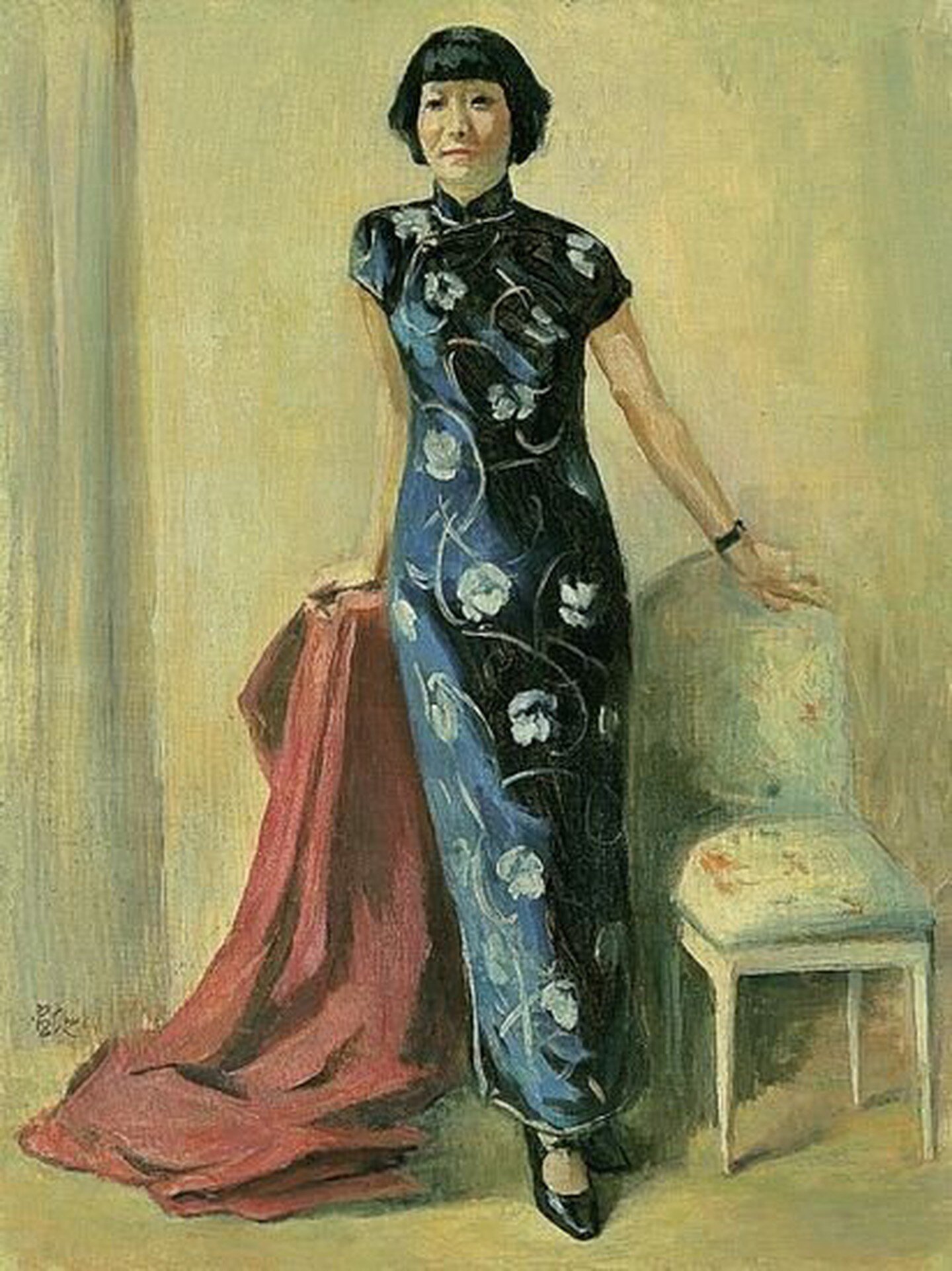

I wanted to understand my cultural heritage. As a woman from Pakistan, I always wondered what my ancestors wore and how they were like. Not having any images as reference for my project, I conducted thorough research at the Decker Library (Baltimore, MD, U.S.) I was able to find the image on the left of a woman wearing the Persian jacket that I aspired to replicate.

For me, going back in time, sewing, wearing, and experiencing what my ancestors wore in the past means a lot to me. I am super happy with how the jacket turned out to be.

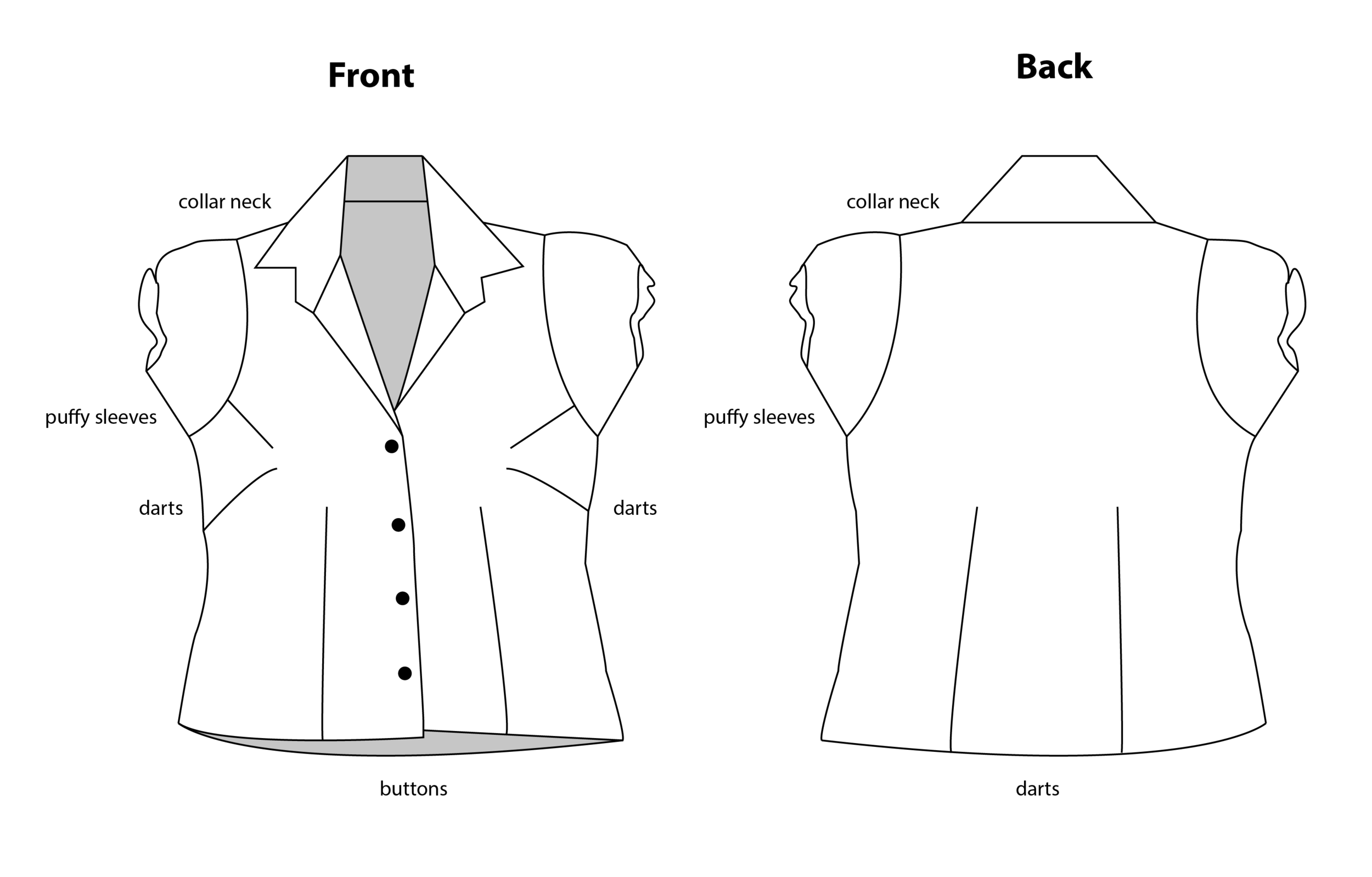

CAD Pattern Drafts

Exemplar

Final Design

Woman Dhoti Garment

Dhoti is also known as panche, mardani, chaadra, dhotar, or panchay. In simple English, it is a loose trouser. It is derived from the Sanskrit word धौती, which means to cleanse or wash. As a clothing garment, it is fashioned out of a rectangular piece of unstitched cloth around 4.5 meters long that is wrapped around the waist and legs and knotted in the front or the back. It is usually in one solar color but in modern times, a variety of patterns have been used for it. Dhoti is usually worn by males and has originated in India but many women also wear it.

I was very inspired by this garment which is why I wanted to give it a contemporary look by using weathering and distressing techniques such as staining, dyed, painted with ground-dirt as well as bleach.

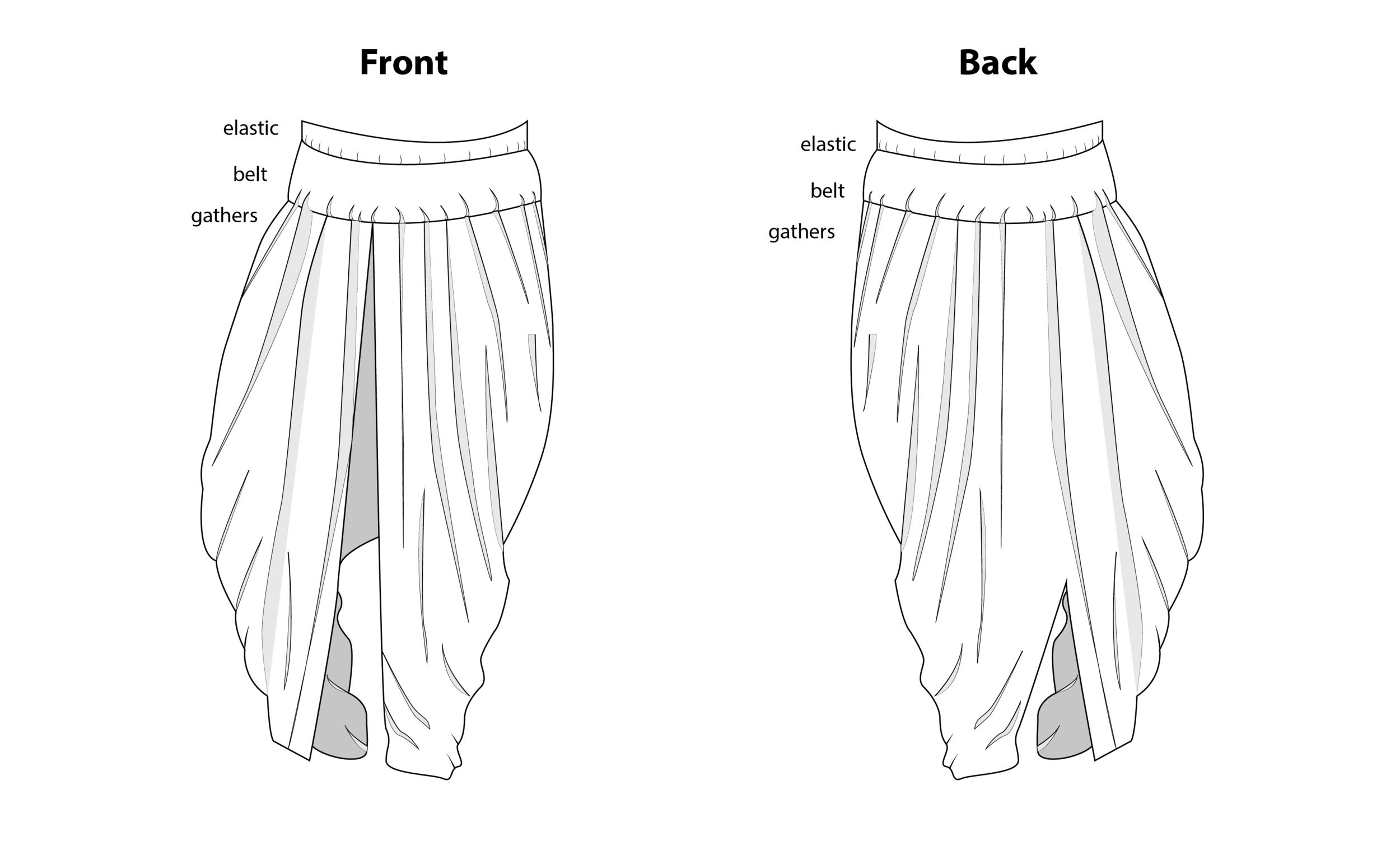

CAD Pattern Drafts

Final Design

Cheongsam Dress

The cheongsam is also known as qipao, which is a close-fitting dress that originated in the 1920s Shanghai. It quickly became the regular outfit of urban women in metropolitan cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. As the garment evolved, traditional silks were replaced with cheaper, contemporary textiles.

The story of the cheongsam started in the Qing dynasty and founding of the Republic of China in 1912. In the mid-1910s and early 1920s, Chinese intellectuals revolted against traditional values. Foot-binding, the painful practice of binding young girl’s feet to prevent their growth, was outlawed during that time as well.

As women were allowed into the education system starting in the 1920s, becoming teachers and university students, they shed the traditional, ornate robes of the olden days and adopted an early form of the cheongsam, which emerged from the androgynous men’s garment called the changpao.

Cheongsam eventually became the regular outfit of urban women in metropolitan cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. As the garment evolved, traditional silks were replaced with cheaper, contemporary textiles. In terms of design, the traditional embroidered florals remained widespread but geometric and art deco patterns also gained popularity.

Through the 1930s and 1940s, the cheongsam continued to change, accentuating the femininity and sexuality of the urban Chinese woman. The dress became more fitted and body-hugging, with some daring designs featuring side slits that reached up to the thigh. Women experimented with different fastenings, pipings, and collars, as well as short-capped sleeves, long sleeves with fur-lined cuffs, and sleeveless cheongsams.

However, shortly after the rise of the Communist government, the cheongsam, which was considered bourgeois, disappeared from everyday life in mainland China. In Shanghai, the birthplace of the cheongsam, the streets were patrolled to ensure that nobody wore fashionable clothing. The egalitarian ideology espoused by the Communists led women to adopt a tunic consisting of a jacket and trousers similar to the men’s.

Nevertheless, the cheongsam’s popularity continued in the British colony of Hong Kong, where it became everyday wear in the 1950s. Under the influence of European fashion, it was typically worn with high heels, a leather clutch, and white gloves.

By the end of the 1960s, the popularity of the cheongsam declined, giving way to Western-style dresses, blouses, and suits. These mass-produced Western clothes were cheaper than handmade cheongsams, and by the early 1970s, it no longer constituted everyday wear for most Hong Kong women. However, it remains a significant garment in the history of Chinese women’s fashion.

I wanted to try and stitch my version of the cheongsam dress exemplar for my reference if I needed to make one for myself with the right fabric in the future.

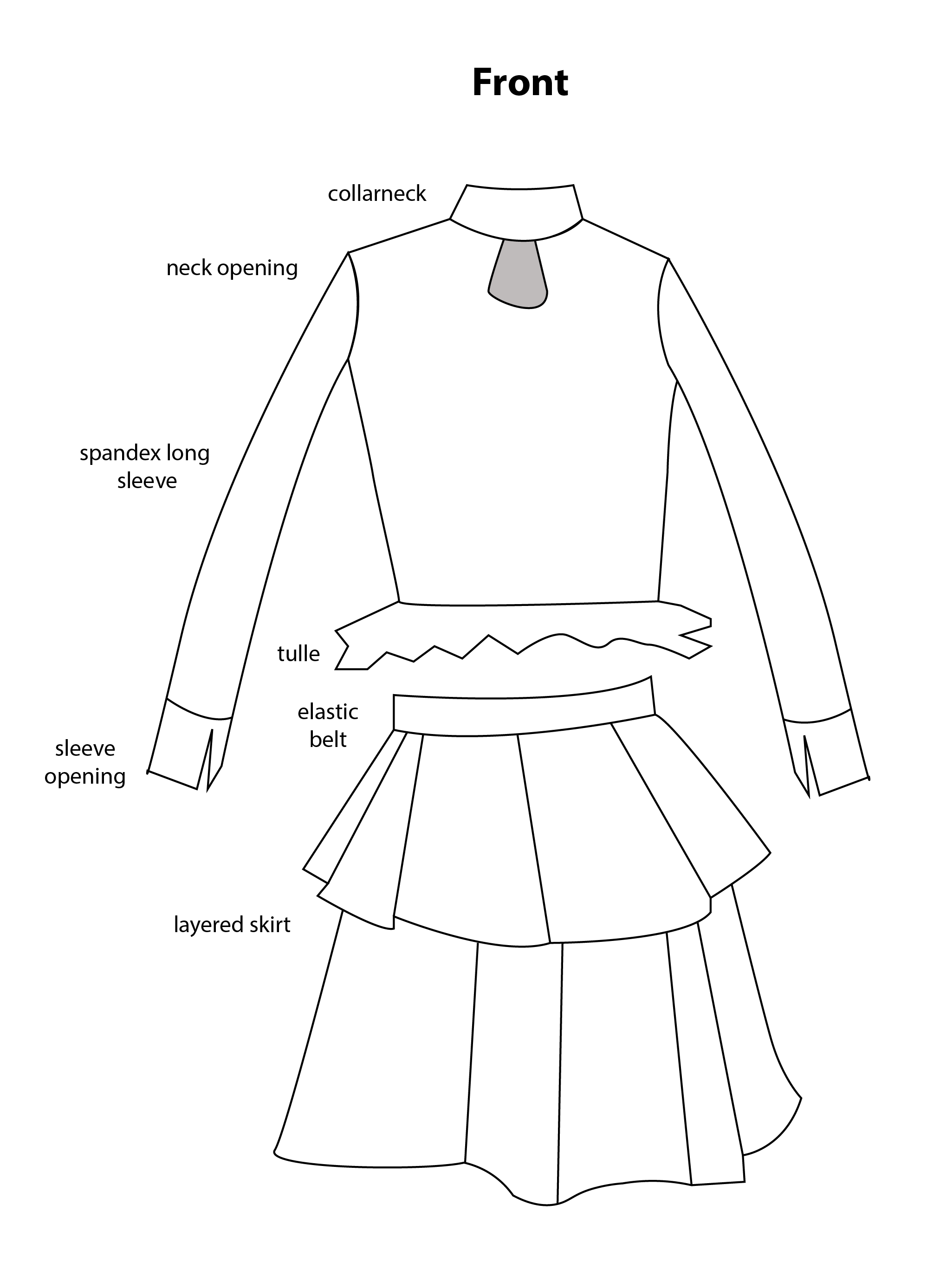

CAD Pattern Drafts

Exemplar

Dress of Kali Goddess

The pictorial representation of Mother Kali is, at first glance, strange and bizarre to the eyes and minds of westerners. Kali is the personification of that aspect of the Divine Mother that compassionately destroys the ego. To begin with, the concept of destroying the ego is not prevalent in western culture.

Kali comes from the root Sanskrit word kala, which means time. Tibetan Buddhism embraces a similar figure as Maha Kala though he is male in gender. In an academic sense, Mother Kali is the primordial energy that animates space and is perceived by us as the linear sequence of events (time). Her skin is midnight blue, almost black, which represents the womb of existence. This is the quantum world of unformed potentials and probabilities, from which all phenomena continually arise and into which they continually disappear.

Her hair is long, black, disheveled, and flowing freely depicting her freedom from convention and the confines of conceptualization. Her eyes are open wide, eternally awake, blazing with the fire of infinite suns as an expression of her indomitable intensity. She is standing, dancing, on the pure white chest of Lord Shiva, who, as pure primal awareness, lays in a passive reclining position, peacefully reposed with his eyes half open in a state of bliss.

Her two right arms are raised benevolently with palms extended, granting gifts of insight and wisdom to her children. Her upper left arm holds the sword of enlightenment, which delivers the blow of non-dual reality to the ego releasing the soul forever from the tyranny of deluded self-intoxication. In her lower left hand, she holds the severed head of the ego. Identification with the body is what gives rise to the illusion of the "I" or ego. Thus, the seemingly gruesome presentation of a severed head depicts the most direct act of sublime compassion, which is bestowed by the mother to her devotees.

Taking inspiration from her existence, I wanted to create a dress that depicted her.

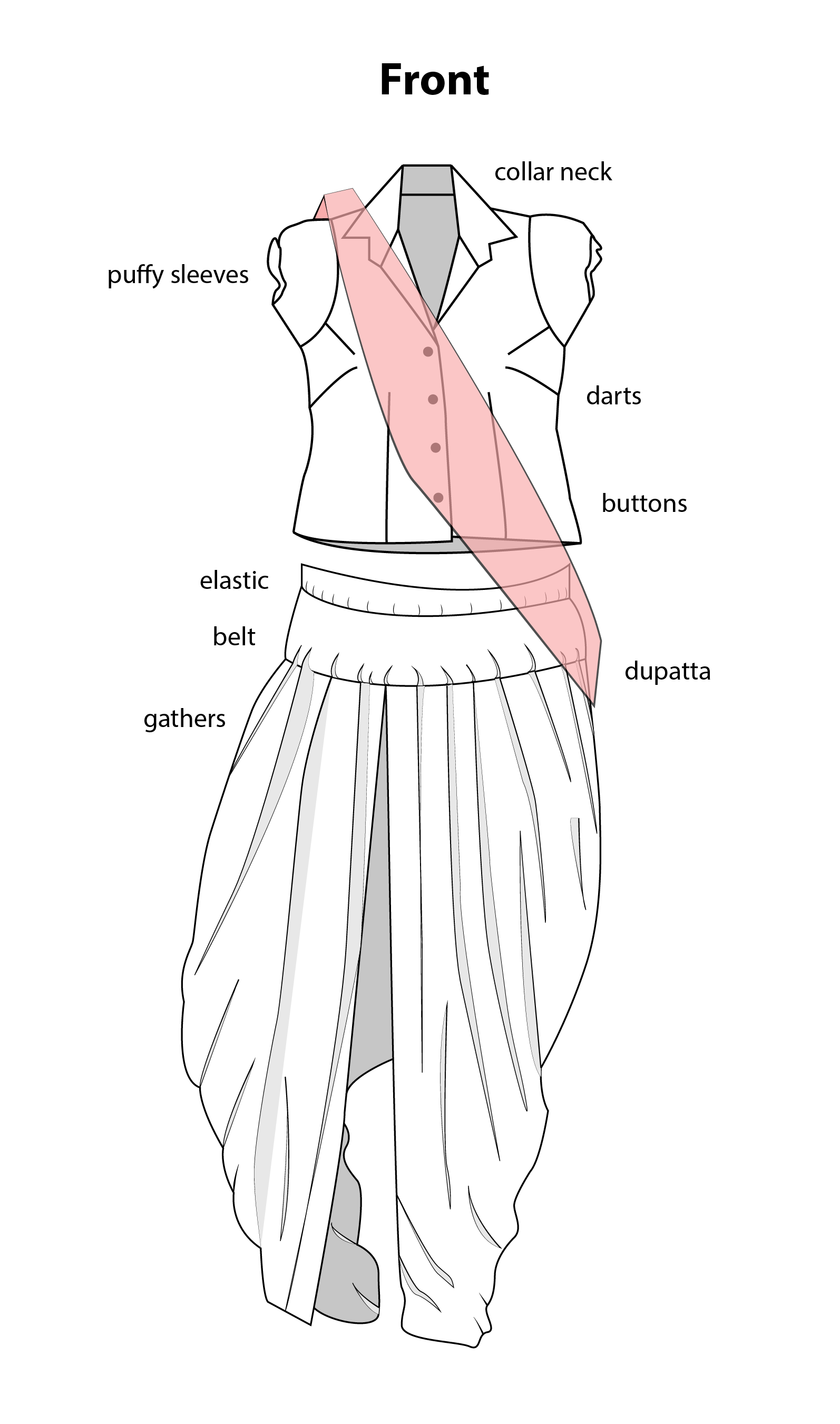

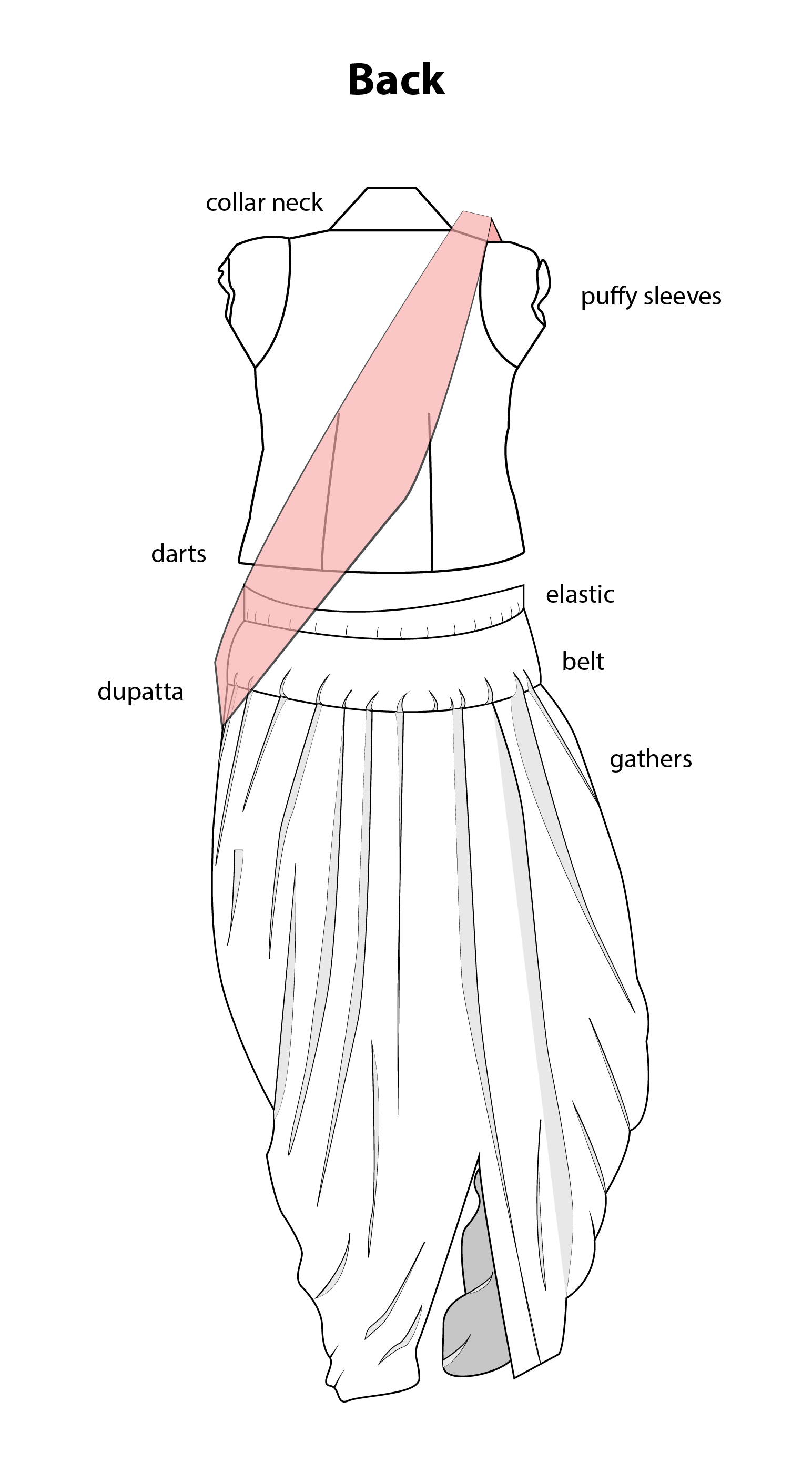

CAD Pattern Drafts

Final Design